I first considered writing an article to discuss strictly MIL-STD 1916, Department of Defense Test Method Standard: DOD Preferred Methods for Acceptance of Product (see PDF file attached to this article). That standard replaced MIL-STD 105 and it is often quoted when discussing statistical sampling, but often with unrealistic expectations. I know what you are thinking, another statistical sampling article? I just can’t seem to get away from the subject. Anyway, I started to dive into the standard in order to explain how it is most useful and when it is more appropriate to stick to general, and more basic, statistical methods when I found myself reading about reliability engineering.

Do reliability engineering concepts apply to inventory accuracy? Do they apply to any business process? It turns out that they can, and there are concepts such as Markov Decision Process (MDP) that are often applied to business.

If we consider physical inventory control as our system, then we can see how that system exists in one state at a time that depends on a previous state (like a Markov chain). The system, most of the time, relies on transactions that themselves have a probabilistic outcome that would have an effect on the state of our inventory. For instance, if 2% of receipts and issues posted are in error.

This brings back some memories. I once wrote a paper on how a logistics information system can impact operational readiness (Ao) and how optimizing the information system could have a more beneficial impact on operational readiness than increasing the reliability of individual weapons systems, because improving Mean Logistics Delay Time (MLDT) improves Ao for all associated weapons systems, even those that have not yet been invented.

It is the same concept with physical inventory controls. The system for managing the inventory, including transactions, policies, and procedures can have a more significant impact on inventory accuracy than any other physical attribute or strictly inventory-related activity.

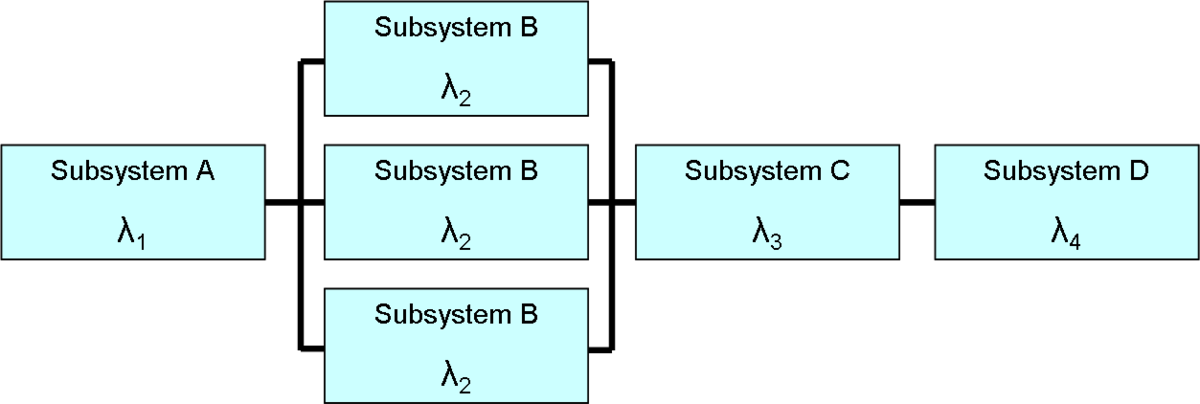

What does that mean exactly? That there are other blocks in the chain that we need to consider. For example, procurement transactions, database maintenance actions, etc.

So what does that mean for MIL-STD 1916? Although it would not be wrong to apply MIL-STD 1916 to statistical physical inventory sampling to measure accuracy, one would still have to get their hands dirty (sort to speak) in order to analyze and extrapolate the results in a way that they provide us with a measure of our inventory accuracy for our entire population. In order to measure our results to see if we meet DoD guidance, we would still need to compute sample size, margin of error, and confidence intervals using basic statistical processes, even if relying on tables and methods from MIL-STD 1916. That military standard lends itself more to what engineers and reliability analysts refer to as “zero accept, one reject” methods (see this paper by Al-Refaie and Tsao (2011)).

So, to tie back to the MDP concept, MIL-STD 1916 absolutely has a place in physical inventory controls, but most especially in evaluating the reliability and acceptability of the transactional processes that are part of our inventory reliability chain. In other words, testing each block in the chain of processes that affect inventory, such as receipt, issues, transfers, etc. is an excellent application for this type of statistical analysis.

Book recommendation of the month. Well, not really a recommendation, but a suitable reference to the above article: Modeling for Reliability Analysis: Markov Modeling for Reliability, Maintainability and Supportability by Jan Pukite & Paul Pukite. Buy a used copy for $10, the book is not worth the full sticker price.